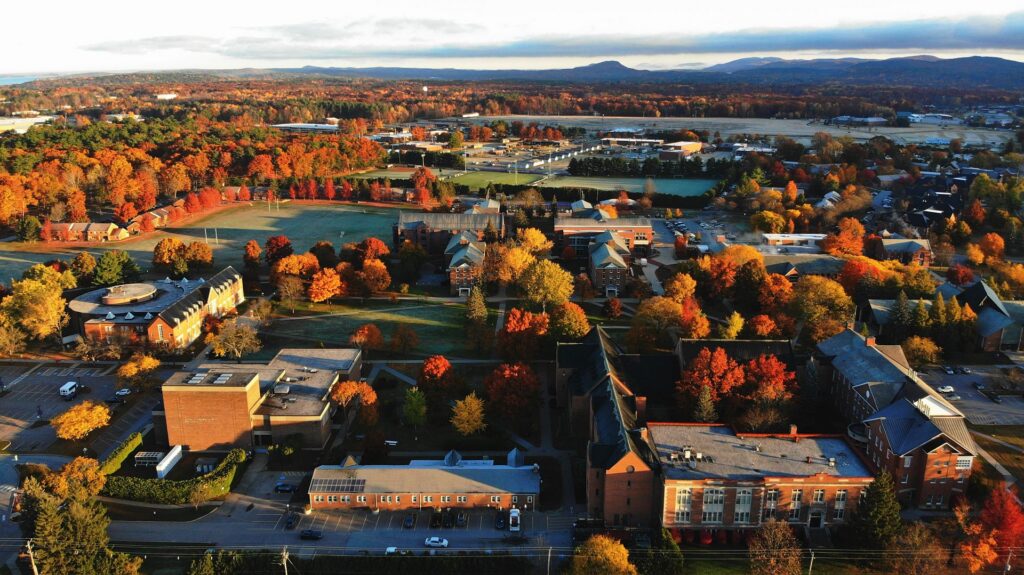

An award-winning freelance photojournalist originally from Moscow, Russia who documented tensions between Russia and Ukraine between 2014 and 2019 recently came to Saint Michael’s College to display his photographs to the community.

Award-winning freelance photojournalist Dmitri Beliakov. (Photo courtesy of Dmitri Beliakov)

Dmitri Beliakov’s photos were on display from the end of October through mid-November on the third floor of the Dion Family Student Center. On Nov. 11, he also gave a talk titled “Putin’s War in Ukraine: How the West is Failing Kiev.” His talk clarified events that led up to the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War and explained why it’s important to document and witness conflicts like that between Russia and Ukraine.

Beliakov’s exhibit and talk were c0-sponsored by Saint Michael’s College’s Department of Digital Media and Communications and the Institute for Global Engagement.

Beliakov has worked for top world media outlets and has had his work appear in publications such as The Sunday Times Magazine, Newsweek International, the Wall Street Journal, Russian Reporter Magazine, American Photo Magazine, the New York Times, National Geographic Magazine, Forbes, and others. He has covered seven conflicts, including the war in Donbass, which forms the basis of his exhibit at Saint Michael’s. The exhibit featured more than 50 of Beliakov’s photographs.

Beliakov relocated to the U.S. after the invasion of Ukraine when Russian parliament passed laws in February 2022 that would likely have resulted in his arrest and imprisonment. He was named a Research Fellow with the Peace and War Center at Norwich University in Vermont shortly after his relocation.

Beliakov recently answered questions about his experiences and the importance of photojournalism in conflict zones. His remarks have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about yourself and your background.

I was born in the north of Russia, Vologda region, and my parents relocated to large regional center of Yaroslavl where I graduated from a special English school and later obtained a diploma of foreign languages department of a local university.

What was it like growing up in Moscow, and how did your upbringing affect your career path?

I did not grow up in Moscow and relocated to the capital of Russia in 1993 when I suddenly found an internship at The Daily/ Sunday Express newspapers Moscow bureau. My decision to become a journalist was shaped between 1993-1994 because I quickly saw the advantages: free travel opportunities; networking opportunities; interesting money and potentially exciting career – an opportunity to be somebody special.

One of the photos shown in a photography exhibit at Saint Michael’s College by award-winning photojournalist Dmitri Beliakov from Oct. 30 to Nov. 14, 2024. (Photo courtesy of Dmitri Beliakov)

What motivated you to become a war photographer?

I never intended to become or even work exceptionally as a war photographer. Apart from covering armed conflicts, I also covered steel, oil and gas industry of Russia; Russian ballet; Russian prisons and labor camps; drug dens across Russia and some parts of the Soviet Union; psychiatric asylums across the former Soviet Union; as well as night life in Moscow and big Western celebrities (Tom Ford, Jeremy Clarkson, Andrei Konchalovsky, Ed Snowden) and their activities in Russia.

Actually, I never called myself a “war photographer.” I am most likely “anti-war photographer” because I hate wars with every fiber of my being.

In your view, what is the role of a photojournalist in conflict zones?

The photographers (as well as cameramen, researchers, etc.) fulfill an important social mission: we increase the awareness of the audience on the issues of our community to make sure that no one says, “We did not know of such and such problems, we were not informed.” Sometimes this is concerning very sensitive issues like war crimes, atrocities and other human rights violations. What has been happening in Ukraine since 2014, and what is going on right now is another example of the importance of photojournalists (as well as other reporters and researchers who document war crimes and atrocities).

Could you describe one of the most memorable or challenging moments you’ve faced while documenting the conflict?

The Beslan school massacre of 2004 was the most crucial moment of my entire career. Through the course of battle between the hostage-takers and Russian special forces, I took a series of pictures of a child who escaped terrorists and attempted to reunite with mother. It took a week of drastic search to find out what happened to the child. We were incredibly lucky to find Aida Sidakova, a 6-year-old little hostage, alive.

One of the photos shown in a photography exhibit at Saint Michael’s College by award-winning photojournalist Dmitri Beliakov from Oct. 30 to Nov. 14, 2024. (Photo courtesy of Dmitri Beliakov)

What are some of the most significant risks you’ve encountered, and how do you mentally prepare for them?

I took countless stupid risks when I was inexperienced and well-calculated risks later. I am not proud of any of them. I have had about six close shaves through 28 years of career and was just very lucky, but if anything at all went wrong, my family would suffer, and this is not worth it.

How do you balance documenting the reality of war with your personal safety?

You don’t have to (and don’t need to) take solid risks when “documenting war reality.” Most of the time when you are there, the stories and pictures are right under your feet – all you need to do is to be able to actually see them, then put together a puzzle, identify the essentials and tell the story.

What are you hoping people take away from your photography?

That it’s the privilege – to see, to capture, to make a difference. It’s small… but who cares.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.