‘Representation matters’: Ed Department raises voices of Asian American women through Common Text program

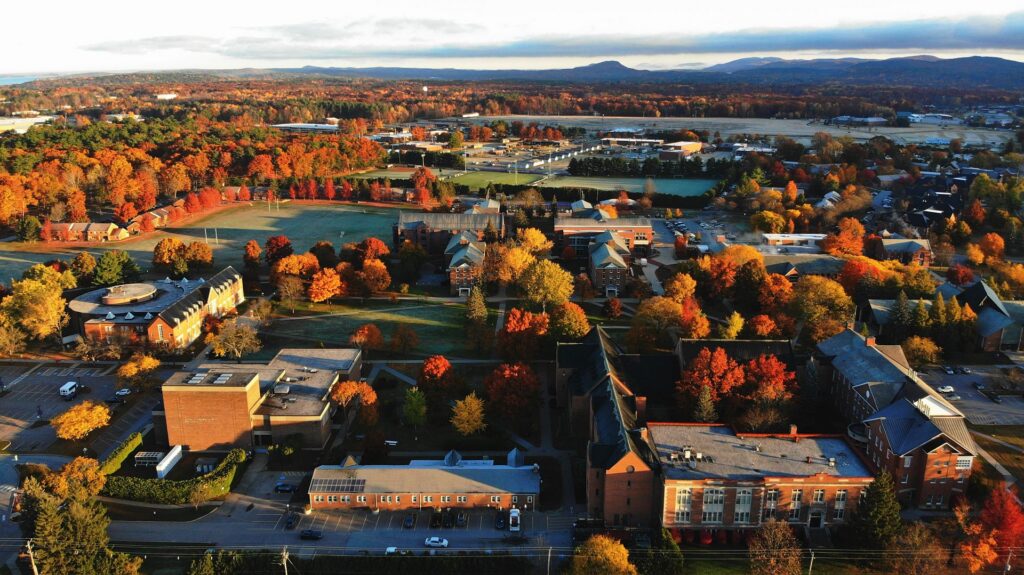

Saint Michael’s Education Department chose to highlight the voices of Asian American women this year for its 11th annual Common Read, a program that identifies a book of importance for all undergraduate and graduate Education students to read and use for reflection and discussion.

Kelly Yang (Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

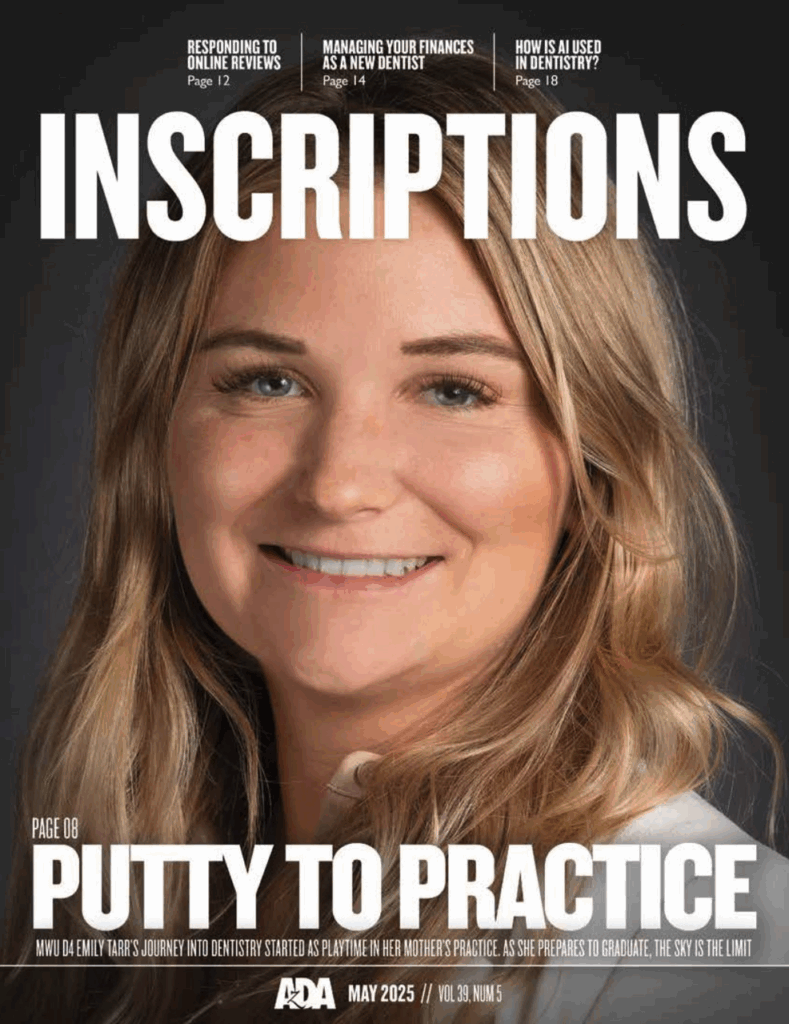

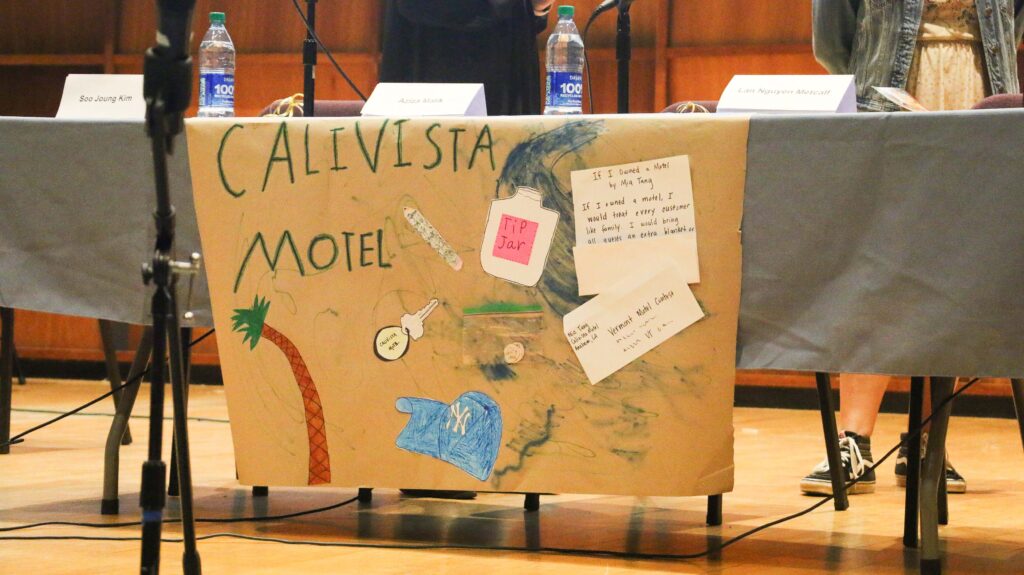

The culmination of this year’s program happened on Oct. 19 during an event featuring a panel discussion by Asian American educators in Vermont and a talk by Kelly Yang, the author of this year’s Common Read Program selection, Front Desk. Education Professor Rebecca Eunmi Haslam moderated the panel discussion before Yang spoke via Zoom to an audience of students, staff, faculty, and other local educators.

Front Desk was Yang’s debut novel in 2019 based on her experience as a child running the front desk of a motel owned by her parents. Yang and her parents immigrated from China when she was a young girl. The book addresses rich and relevant themes including racism, social class, immigration, and more, much of which is grounded in Yang’s own life experiences.

Before Yang spoke, the panel of local Asian American educators shared their own experiences and how they related to the book. They also discussed ways they have worked to ensure bias stays out of their classrooms and how they have focused on fostering antiracism and equity. The panelists included:

- Lan Nguyen Metcalf, a teacher at Enosburg Falls High School.

- Aziza Malik, a teacher at Champlain Elementary School who was recently named the 2024 Teacher of the Year in Vermont.

- Dr. Soo Joung Kim, Professor of Education at Saint Michael’s College.

(Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

Representation matters

In introducing the panel, Professor Haslam asked the audience whether they had seen so many Asian Americans on stage at one time. She said it was worth pausing to think about why this matters and what it means to raise the voices of people who have been historically marginalized. Haslam is the coordinator of the College’s Racial Equity & Educational Justice Graduate Certificate Program.

Professor Rebecca Eunmi Haslam (Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

“Representation matters, and lack of representation matters,” Haslam said. “If you’ve never seen Asian folks at the front of the room, you might wonder if we actually have anything of substance to offer.”

Haslam said the choice to specifically raise the voices of Asian American women was intentional. Many are still unaccustomed to “seeing Asian women take up space, hearing our voices and hearing them loud, expecting to hear our perspectives.”

The teachers on the panel discussed assumptions about Asian Americans they’ve witnessed or faced themselves, relating those experiences back to Yang’s book. Dr. Kim encouraged people to refer to people who do not speak English as a first language as “multicultural learners” and not as “English language learners.” This distinction is important, Kim said, because it shows that a student’s first language is an asset and that their temporary inability to speak English does not make them less smart than English-speaking students.

Dr. Soo Joung Kim (Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

Kim faced this double standard when she immigrated to the U.S. and began to attend school. She told the story of how a school counselor placed her and her twin sister into a lower-level math class after assuming they couldn’t do high-school-level math because she couldn’t speak the language. She and her sister later surprised their teacher when they aced several practice math tests.

“He was surprised, and I was so proud,” Kim said. “I was also sad because I was like, ‘What are they thinking?’”

Lan Nguyen Metcalf (Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

Nguyen Metcalf related. Assumptions were made about her own intellect because she has a facial birthmark and because she is Asian. These assumptions are harmful, she said, especially since they happen over and over again.

“I stand out in lots of different ways,” Nguyen Metcalf said. “I’m still caught off guard by the number of people, strangers, that I meet who speak to me really slowly.”

Nguyen Metcalf and Malik also discussed their experience of being automatically grouped with other minority students since teachers and other students just assumed they were close friends because they shared a similar ethnic background. This was not always the case – an experience also reflected in Yang’s book.

Aziza Malik (Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

“When I got to high school there was one other Indian girl, and everyone assumed we would be friends,” Malik said. “We were not even close to being friends, and it was just interesting how we were always lumped together in that way.”

Creating a character for others to identify with

Before writing Front Desk, Yang had never told anyone about her experience of running the front desk of her parent’s motel as an 8-year-old with limited English. She was so scared, even into adulthood, of people knowing this secret she had kept for so long. But, when her own children began to get older, she decided it was time to write the book so at least they could know her story.

After writing each chapter, she would read it with her son, “whose mind was blown” by the story, she said.

“Even though there was a lot of poverty and there were definitely hard times, there was also so much joy and so many amazing experiences that make you feel totally human and alive,” Yang said. “I wanted to just capture the magic as well as the hardship.”

Yang’s son soon encouraged her to submit her manuscript to a publisher. As someone who rarely found books with Asian characters or authors while growing up, Yang agreed to try.

(Photo by Elizabeth Murray)

Yang said she had no expectations when Front Desk was finally published. She was overwhelmed by the number of letters and messages she soon received from people saying how her book resonated with them and gave them the courage to tell their own stories and embrace their heritage.

“I just really did not want the world to laugh at me,” Yang said. “Instead of the world laughing at me, it gave me a whole bunch of awards. … I didn’t really know it was going to impact so many people.”

At the same time, her book was swept up in some of the efforts across the U.S. to ban certain books for children. Often, these books have diverse characters or represent marginalized identities. Yang fought back against one such decision via a video on social media, which resulted in the school district’s superintendent reversing the ban within 72 hours.

“It really starts with every single one of us speaking up,” Yang said.

About the Common Read Program

The Saint Michael’s College Education Department’s annual Common Read program committee identifies a book of importance each year to share with students in both the undergraduate and graduate Education programs. The book selected each year speaks to the department’s mission statement, which includes a commitment to holistic education, antiracism, equity and justice as well as creating sustainable communities and schools. The book selection – serving as a model for the power of literacy – provides a basis for discussion and learning throughout the year. The Common Read program and the community mural also serve as resistance to efforts around the country to challenge or ban books for children and young adults.

More information about the College’s Education Department can be found here.>>

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.