Krista Billingsley, Director of Criminology and Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Criminology, presented on Monday as part of the social science seminar series. Billingsley conducted field work in Nepal over 14 months primarily in 2016. After she became a professor at Saint Michael’s, she helped create a follow-up collaborative film project in Nepal that was focused on victim-led, truth-telling.

Krista Billingsley (Photo by Cat Cutillo)

Nepal had an armed conflict from 1996-2006 between the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) and Napoleon Government, Billingsley explained during her presentation. In 2006, the peace agreement was signed which ended the armed conflict. Part of the peace agreement included “mechanisms of transitional justice,” which she said are things implemented to try and address human rights violations during the armed conflict.

“No one has really been held accountable in the way that we think about punitive justice. There’s not been trials,” Billingsley said.

Billingsley explained that transitional justice engages international human rights law and humanitarian law. She said one of the mechanisms used was something called “Truth Commissions,” which are argued to be more victim-centric. Truth commissions give victims the ability to tell their story about what happened during the armed conflict to establish a document that is the truth.

“There were a lot of people who were ‘forcibly disappeared’ during the armed conflict. People were taken and held incognito. Their families have never seen them again,” Billingsley said.

Krista Billingsley (Photo by Cat Cutillo)

Billingsley conducted research in two districts in Nepal in 2016. After she returned home from the field, she applied for a grant to partner with scholars and create a film that would engage the children and people who were forcibly disappeared. The victims participated in the co-creation of the project to tell their stories through film and memorialize their loved ones who were lost through the armed conflict. The victims then determined where their stories would be disseminated.

“They wanted their stories told. They wanted their loved ones remembered,” Billingsley said and explained that people wanted to correct misinformation. “Even after all of these years, there’s this idea that their family members were disappeared because they did something wrong and they don’t want that to be the legacy of their loved ones.”

When Billingsley was asked during the presentation what her biggest challenges were, she said, “This is hard work, especially if you care about it.”

She explained that she worked with people who were children when the armed conflict happened and some of them were tortured.

“People shared a lot more than I asked about. That was difficult hearing the details,” Billingsley said. “I was trained for this, but it’s still hard to hear.”

Billingsley made a point to end her presentation on an up note.

“There is hope. It’s about resilience. It’s about joy. It’s about people who will stand up to a state that has targeted them,” Billingsley said. “It’s a heavy topic.”

Right to Truth Day-Kathmandu March 2016 (Photo by Cat Cutillo)

(Photo by Cat Cutillo)

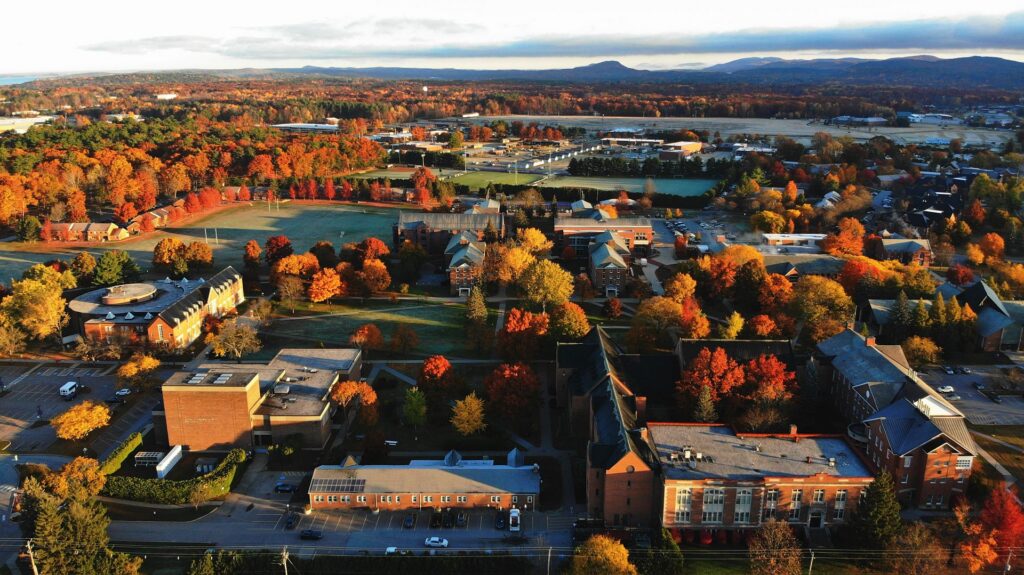

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.