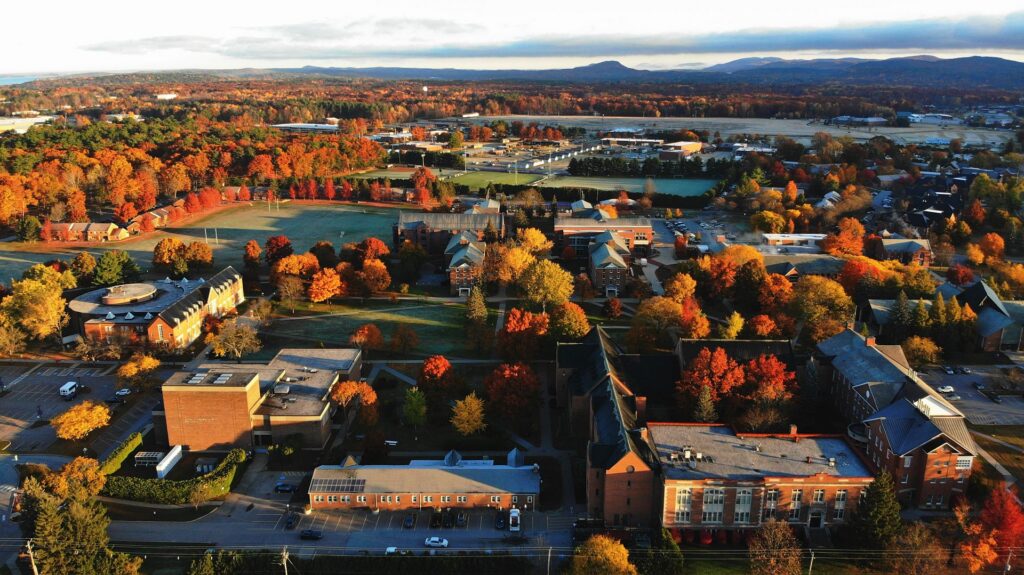

For the second time ever, first-year students at Saint Michael’s College were able to take a seminar class taught by disability rights advocate Sefakor G.M.A. Komabu-Pomeyie called Peace and Justice: Disability.

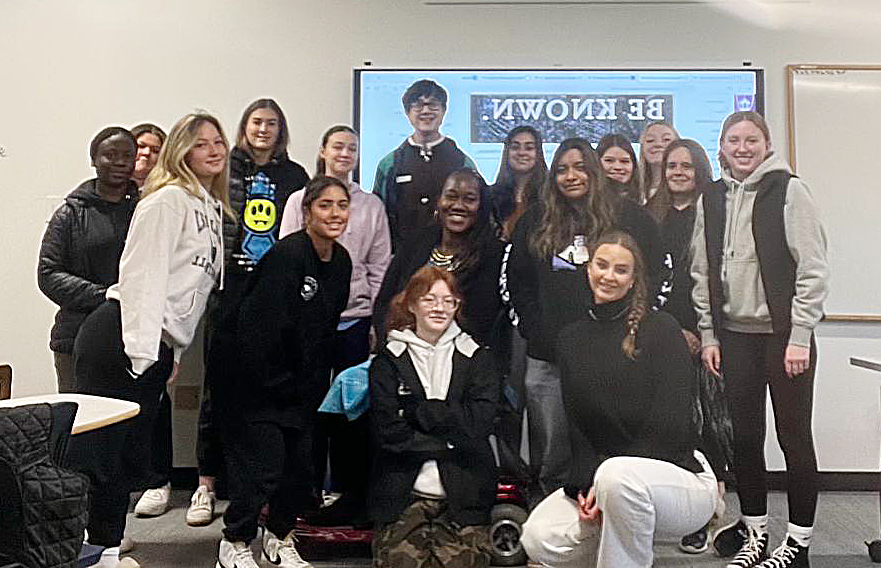

Peace and Justice: Disability class at Saint Michael’s (courtesy photo)

Komabu-Pomeyie, an adjunct instructor at Saint Michael’s originally from Ghana, has served as an international disability rights advocate, educator, researcher, and policy analyst for the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD), and as the Resource Center Coordinator of the Ghana Education Service. She has been a staunch supporter of inclusive education for people with disabilities and lobbied successfully with other advocates in Ghana for the establishment of the Disability Law (Act 715) of Ghana as well as the ratification of the UNCRPD.

“In this class, I decode disability. I dismantle it,” Komabu-Pomeyie said. “I pave the way for the student to really understand what it means to have a disability as part of our identities.”

The class discussed eugenics and how people with disabilities were sterilized in history to prevent them from procreating. They discussed the power of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Komabu-Pomeyie also taught her students disability policies from Africa and around the world.

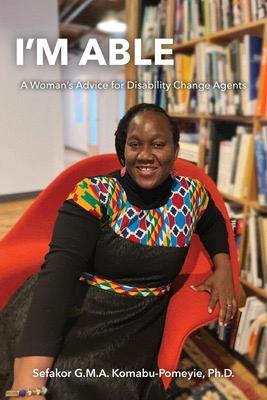

At Saint Michael’s, she teaches an ethical leadership with disability policy class for graduate students during the summer. This spring, she will be teaching one session of a Purposeful Learning course. She also teaches Global Disability Studies and Race and Racism at the University of Vermont as an adjunct instructor. In September, she published the book I’m Able.

“I’m a person with physical disability myself and use a wheelchair or a scooter,” Komabu-Pomeyie said. “When people hear about disability, they always think of those of us who have a physical disability.”

She explained that she helps students dismantle the negative perceptions around having a disability and, instead, embrace disability as part of humanity. With this, Komabu-Pomeyie, people can fight for disability justice with a human face or connection.

Of the 15 students who took the class this fall, Komabu-Pomeyie said many of them went through a personal exploration, and some discovered that they themselves do have an invisible disability.

Declan Heney ’27 is double majoring in Elementary Education and Psychology and took the class as a first-year seminar. Heney said he lives with generalized anxiety disorder.

“Before this class, I didn’t know it was a disability,” Heney said. “I learned I do have a disability, an invisible one.”

For his final presentation, Heney chose the topic of an athlete’s mental health. Heney played sports in high school and has a passion for ice hockey. He was interested in the topic because athletes are often told to “shut it down” and suppress their feelings.

“The stereotypical athlete is strong, athletic and has no problems. That is clearly just not the case,” Heney said. “It’s a really amazing class and I really benefitted from it.”

Komabu-Pomeyie said people with invisible disabilities like anxiety and dyslexia are often overlooked. She incorporated disability pride into the curriculum to encourage students to be proud of their disabilities and other issues of intersectionality.

“My students are all ambassadors and have to take the message across to educate people who are at the denial stage not accepting who they are,” Komabu-Pomeyie said.

Last year, for example, Komabu-Pomeyie said she taught an international student whose family wanted him to hide a disability he had just discovered he had due to their cultural beliefs.

Sefakor G.M.A. Komabu-Pomeyie

“I had to help him to go for counseling and assessment to have reasonable accommodations,” she said.

As part of her class, Komabu-Pomeyie shares her own story with the students.

“I was neglected by my own father,” said Komabu-Pomeyie, adding that she got polio when she was 8 years old. She said her father left a note on the table for her family before leaving them.

“Because in my culture, they believe when you have a disability you are cursed,” Komabu-Pomeyie said. “You are bringing a lot of negative curses to the family so my dad had to run away from us.” Komabu-Pomeyie said, “This negative attitude still exists in the American system too because some people still see people with disabilities as unproductive, useless beings, and burdensome.”

She also shares with the class the experience of losing her daughter eight years ago – a twin to her son, now aged 15.

“I share these stories to let them know that they are not alone and we can still be happy and productive in our journeys despite all odds,” she said. “I still have hope. I still have peace and comfort within me which I still give to people based on the fact that I believe I’m not cursed like my dad thought.”

Komabu-Pomeyie said she aims to create a class environment that allows students to support each other to explore very personal experiences around disability.

“We build a family in the class,” she said. “I call them ambassadors, so they know they are ambassadors for the class.”

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.