Professor Declan McCabe of the Saint Michael’s biology faculty presents about biodiversity Tuesday in the McCarthy Recital Hall. The large image behind the headline shows McCabe’s colleague Ruth Fabian-Fine introducing him. (Photos by Patrick Bohan)

What happens when certain species disappear from the Earth, and what can we do to prevent that from happening?

Those questions were at the center of a presentation by Saint Michael’s College Professor Declan McCabe titled “The Biodiversity Crisis and What We Can Do About It,” the evening of April 18 in the McCarthy Recital Hall during Earth Week 2023.

Throughout the presentation McCabe aimed to equip attendees with ideas for managing the worldwide biodiversity crisis in which we find ourselves – exploring both individual choices and international policies that could make a difference. There is no “us and them,” McCabe said as he explained the wide impact that species losses can have on the world. “Humans and nature are one, and we sink or swim together… “We have caused the problem, and we must take ownership of the solutions.”

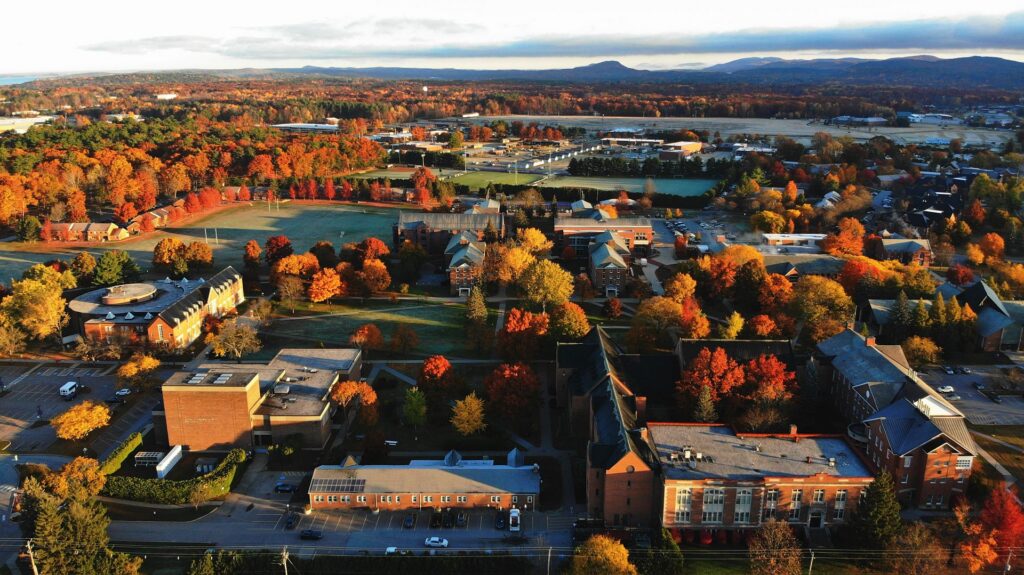

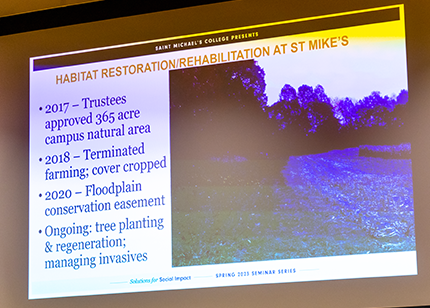

McCabe also discussed the number of solutions applied on Saint Michael’s campus to illustrate the straightforward actions that all humans can take to reduce biodiversity loss and rehabilitate habitats. The 6 p.m. presentation was part of the ongoing seminar series “Solutions for Social Impact” — and also was viewable via livestream as with other presentations in this series.

The event was one of the activities planned for Earth Week on the Saint Michael’s campus, which also includes a large-scale tree-planting project that will take place at the end of the week – something McCabe mentioned and encouraged people to join at the start of his presentation.

McCabe’s biology faculty colleague Ruth Fabian-Fine introduced the speaker, who then used PowerPoint slides to illustrate his key thoughts during a talk that lasted just over an hour, leading into a short question-answer period.

He started by defining terms on biodiversity and ecosystem diversity, explained about species’ extinction, humans’ role in that, and ethical questions such as “Do species have the right to exist?” McCabe feels “we have a lot of gall destroying some of them.” Some species are extinct in the wild for all practical purpose even if specimens still exist in limited ways. However, McCabe said he “never gives up hope” on species, though “realists rein me in” at times.

One of many PowerPoint slides from McCabe’s presentation.

“We are part of the house of cards,” he said. “There is no ‘nature’ and ‘us’ — we’re all part of the same system so we need to take care of it.”

Some of McCabe’s later points included that “habitat loss is the greatest threat.” He showed slides about how climate change is dramatically shifting where species now are showing up, with many birds, for example, observably moving more north into Vermont compared to even 50 or 60 years ago.

He told the audience, “Only six percent of the combined weight of mammals on earth is wild.” He asked, “What we can do?” and his answer focused on the idea of “rehabbing” habitats since we realistically are past “restoring” habitats in most cases in his view. Yet, even the prospect of such rehabilitation is cause of optimism, he said.

McCabe spoke of earth’s human population nearing a predicted peak in the next century. “We will decline slowly,” he said. One idea from a fellow biologist that he shared is to protect “half of the earth for biological diversity,” which at first might sound extreme. Yet, he asked listeners to “think of oceans” or large undeveloped tracts in Canada that might contribute to this being a hopeful goal.

His recommended approach to a workable solution was to take it it “town by town, yard by yard, campus by campus, church by church” to make a difference. Concrete actions he recommended for anybody who wants to help counter species loss included voting for lawmakers who make environmental issues a priority; taking part in planting initiatives such as at Saint Michael’s, and “educating everybody” about these issues.

Throughout his talk, McCabe continually made Saint Michael’s connections. That included data from biology graduate Janel Roberge ’12 (now a College staff member as Coordinator of Online & Nontraditional Programs) that correlates forested areas and presence of various species. In addition, he showed a Global Eyes photo of what an stream ideally can look like, from a student’s study-abroad time in South Korea. Another dramatic slide showed an image of a bald eagle, from a trail camera in the College Natural Area.

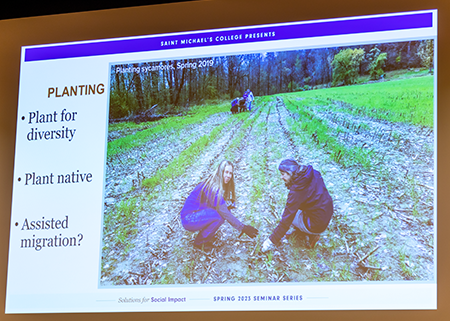

This slide from the presentation shows students planting sycamores in the Natural Area.

McCabe described how bald eagle populations in the U.S. had diminished to dangerous levels in the early 1960s, with fewer than 500 nesting pairs and Vermont the last state to restore any — but a response from human activists, including banning DDT’s and public education by author Rachel Carson, showed that humans CAN make a difference.

With the College Natural Area now, he said, two thirds of campus is natural area. He explained how initiatives of recent years converted it from farmland to its present state supporting many varied species of plants and animals. He said the widespread planting of sycamores has been particularly successful since they thrive in this area.

According to McCabe, one thing we can do is “plant trees that are good for the specialists (among species), and the generalists will also come.” Willows are a great example he said. In addition, “Plant for pollinators, but not just for pollinators,” he further recommended. “We need to plant native species that feed other native species up the chain.”

McCabe spoke also near the end of his talk about invasive species and their significant impact on habitats, particularly the inevitable and fast-encroaching emerald ash borers that are “coming for our 88 [campus] ash trees,” and already are being found right next door. “That’s another reason to plant for diversity,’ he said.

He mentioned, too, the “unlawning” project of fine arts Professor Brian Collier that proposes for humans to “just stop mowing, and other things will grow.”

“Plant early and plant often, and keep planting,” McCabe said.

— Elizabeth Murray ’13 and Mark Tarnacki contributed to this report

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.