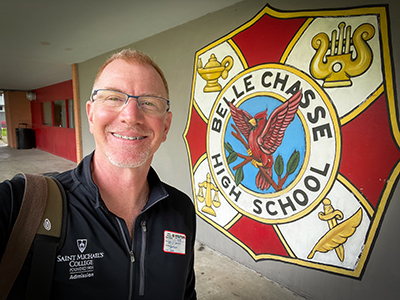

Donald S. Lopez, professor of Buddhism and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan, came to Saint Michael’s College Tuesday night and gave a lecture titled “A Jesuit Missionary in Tibet” in the McCarthy Arts Center through the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholars program.

Donald S. Lopez, professor of Buddhism and Tibetan Studies at the University of Michigan, came to Saint Michael’s College Tuesday night and gave a lecture titled “A Jesuit Missionary in Tibet” in the McCarthy Arts Center through the Phi Beta Kappa Visiting Scholars program.

Saint Michael’s has hosted a chapter Phi Beta Kappa since 2003, one of the few Catholic colleges or universities to shelter a chapter of the prestigious national academic honor society. Lopez’s position in Michigan’s Department of Asian Languages and Cultures, as well as several of his published works, made him an ideal expert for the Phi Beta Kappa chapter at Saint Michael’s to invite through this Visiting Scholar program, launched by Phi Beta Kapp in 1956.

His Tuesday lecture drew upon the speaker’s own extensive work studying Ippolito Desideri, a Jesuit missionary who traveled to Tibet in the early 1700s. A central focus of the talk was the history of Christianity’s relationship with Buddhism. Professor Nathaniel Lew, president of Saint Michael’s Phi Beta Kappa National Honor Society chapter, opened up the lecture gathering and introduced Lopez.

Lopez opened his lecture with the statement, “conflicts among religions are as old as religion itself.” He explained how scholars like himself spend much of their time “rescuing” religions that early Christian authorities and scholars negatively labeled as “idolaters,” such as Hinduism, Sikhism, Confucianism, and Buddhism.

In his lecture, Lopez explained how Buddhism has been one of the only religions largely to escape the harshest Christian negativity of this period and even after, though he did not specifically say (nor rule out) that the Jesuit missionary was a significant reason. In many early Christian missionary texts, Lopez said, “caricature and stereotype” often represent Buddhism, but, Lopez said, scholars use these negative texts not so much to understand Buddhism better as to understand more about their Christian authors.

Lopez shared details from history about Desideri and his years in Tibet among Buddhists and Buddhist monks: The only record of him being in Tibet are this missionary’s own writings, and s no Tibetan sources ever have emerged describing Desideri’s presence there. As a result, scholars do not know with whom he spoke during those Tibet visits.

During his years in Tibet, Desideri wrote a guide with his thoughts on the best way to evangelize Tibet and reached the radical conclusion that Buddhism was more honorable a religion than what he referred to as the “Indian paganism” — what scholars understand to be a reference to Hinduism.

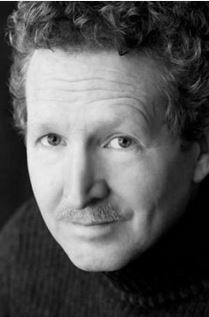

Donald Lopez

The speaker said Desideri labeled and defended Buddhism as a “special paganism.” As the only Christian and only European in Tibet, Lopez said, Desideri wanted to stay there but eventually was ordered back to Rome by the Catholic Church. He faced ridicule upon his return to Italy for his stances on Buddhism. The aspects of Buddhism that he did not understand from a Catholic perspective he labeled as “Satanism” which Lopez sees as interesting given that Desideri was a man known to be devoted to reason.

Desideri spent his time in Tibet learning the language and the Buddhist religion, eventually drawing parallels between the final rebirth of the Buddha and the Christian Nativity.

The Buddha, Lopez said, “is how the Word became flesh” for Tibetans in Desideri’s thinking. To explain similarities between the religions, later scholars posited – wrongly according to Lopez – that those similarities are traceable to the two faiths having encountered one another in history, though Church authorities rejected this notion, preferring to explain this difference as demonic plagiarism.”

Lopez closed his lecture with a translated prayer by Desideri and encouraged the lecture attendees to “focus their minds on Jesus or the Buddha.”

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.