David Dennis Jr., far left, and his father David Dennis Sr. seated beside him, converse with Jolivette Anderson-Douoning Thursday afternoon in on the McCarthy Recital Hall for the 2022 Sutherland Lecture. (Photos by Cam Wilson ’23)

Watch video of the entire Sutherland Lecture event>>

David Dennis Sr. as a young college student already had been one of the first brave “Freedom Riders” in the early 1960s American Civil Rights Movement when a defining moment in Alabama brought him all-in to that Movement.

“We ended up in Montgomery under martial law,” he said of his early group of youthful bus-riding protesters across the then-segregated South, who were meeting up with top national Movement leaders of the day such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Andrew Young and John Lewis in the wake of jarring violence against their protests. “They were all just trying to get the rides to stop” out of concern for the safety of the young riders. Yet, many among the group “kept saying we need to continue,” even though Dennis Sr. wasn’t so sure — until he heard someone in the room say, “There’s not enough space in this room for both God and fear.”

“Boom! That was right between the eyes for me, and everyone said ‘I’ll go.’” Dennis Sr. remembered. “I didn’t stop after that.” It was just one piece of rich living history that an audience of nearly 100 in the Saint Michael’s College McCarthy Arts Center including President Lorraine Sterritt, students, Edmundites and faculty, experienced during the 2022 annual Sutherland Lecture, expressed this year in a different format from traditional solo lectures of the past.

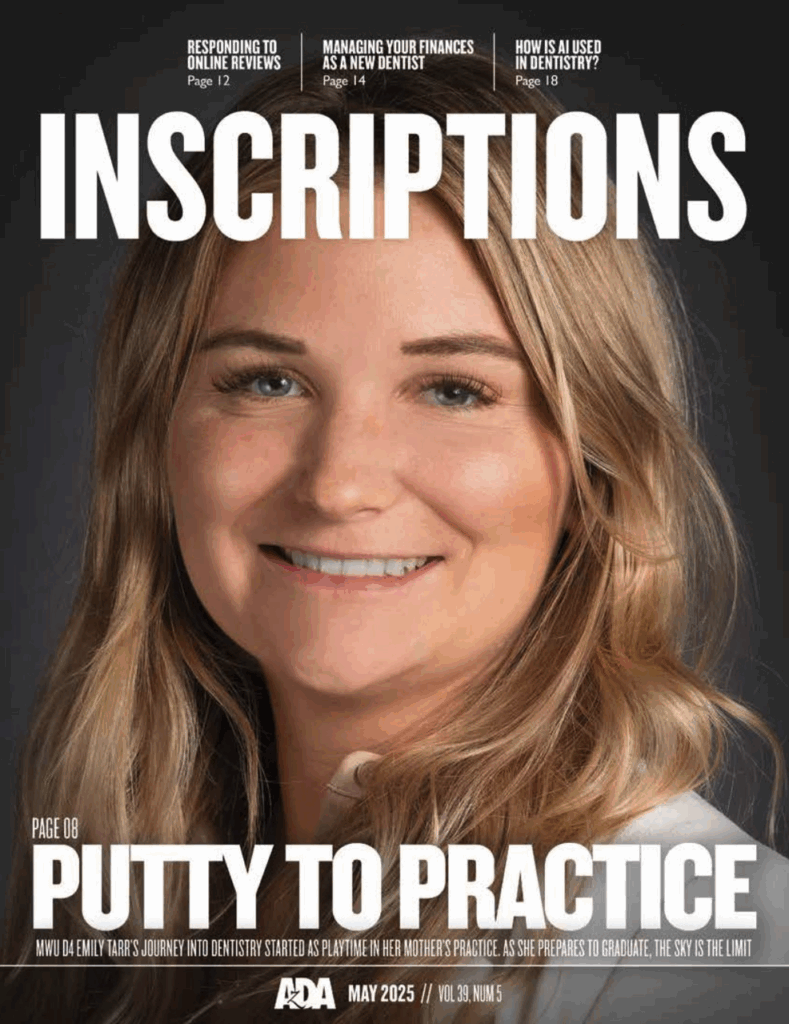

Dennis Sr. and his award-winning journalist son, David Dennis Jr., collaborators on a forthcoming book titled The Movement Made Us, communicate strong and urgent messages through their writing and appearances to fellow Americans about race, rights and democracy in such unsettled and pivotal modern times. Sadly, many are the same lessons that the senior Dennis was standing and riding for half a lifetime ago, the conversationalists acknowledged.

David Dennis Sr. makes a point as his son listens.

The Dennis men took seats on the Recital Hall stage across from the College’s Inaugural Edmundite Fellow Jolivette Anderson-Douoning, who primarily organized this year’s lecture event. True to their spirit, born of the Movement, to inspire, teach and remember the heroes who came before, the guests “never budged” from their mission throughout the host’s thoughtful probing questions, assuring the audience could properly absorb their powerful witness.

This notion of “not budging” references a quote projected on a PowerPoint slide behind the conversation at one point. The host selected words from the writing of the younger Dennis: “No matter how hard racism tries to erase us, we’ll continue to exist and that persistence, the dedication Black people have to not budging – has become one of the most disruptive things we can do.”

Jeffrey Trumbower, the College’s vice president for academic affairs, opened and closed the Sutherland lecture organized by Jolivette Anderson-Douoning, left.

Anderson-Douoning billed the session as a “conversation about the relationship of a father and son and how their lived experiences are deeply rooted within the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and Black Freedom Struggles in the Deep South…” The event opened with Jeffrey Trumbower, vice president for academic affairs, explaining how the Sutherland Lecture is “the College’s premier endowed lecture, set up many years ago by Donald Sutherland and his wife, Denise.” He said Sutherland family members were joining viewers from across the country in watching a livestream of the event as well. Scores of people signed on and many left messages.

Trumbower said that, to show solidarity with horrible events unfolding on TV in the last week in Ukraine, a late addition to the program would be recitation of a “poem for peace” from Rafnii Eddins, who came forward to explain how his mother wrote “Nobody Came” after the 9-11 attacks. In a hypnotic call and response format, with Eddins intoning the lines musically, the audience responded on cue several times, “I’d like there to be a war where nobody came.”

Trumbower then introduced Anderson-Douoning, who invoked traditional rituals of respect from her cultural experiences by seeking permission from elders to speak, saying of the Dennis men, “this is family.” Through the program, she and they connected on close common bonds from their lives and mutual friends, places and experiences in ways that made Thursday’s session almost feel to them, they said, as if it was predestined to occur. A dramatic moment in the conversation came when the senior Dennis became emotional, describing how he had felt the spirit presence of Bob Moses enter the room. Moses, a civil rights giant who died last year, was close to both the Dennis family and to Anderson-Douoning through their Movement work.

Rajnii Eddins presents his mother’s poem “Nobody Came” — a poem for peace.

The senior Dennis built on the opening poet’s theme by saying “I want to talk about a war that I was in that I wish nobody came.” He told his personal history: Born on a plantation in a sharecropper family in northern Louisiana, having the good fortune to attend college at the historically Black college Dillard in New Orleans to study engineering until 1960 when he had inspiration from active friends to join early freedom rides. He was a full-time field secretary for CORE in ’61 and stayed in the Movement until 1965 in Mississippi, spending some time in infamous Parchman prison for some activities. Prominent civil rights leader Medgar Evers was one of his best friends, he said, and the two men talked shortly before Evers was assassinated; also, Dennis Sr. was with the young white voter-registration student activists, Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner, 24 hours before their murder in Philadelphia, Mississippi. “My count is we lost 19 people during that period that people don’t’ talk about – it’s beyond just who you read about,” he said. Dennis Sr. honored the heroism of Black families in Mississippi who hosted white voting-rights workers in their homes in 1964, risking their very lives by doing so.

He and others “didn’t know about a thing called PTSD” but it was real in their experiences, he said. “A lot of us didn’t come out of that unmarked, including me, so I want to talk about where we are today and the impact it has had and why we are at this place in time and what we all have to do about it, because this war has not ended.”

Though their themes often were serious, the Dennis men brought humor and warmth to their conversation Thursday too.

The younger Dennis then took his turn, calling himself “a child of the Movement,” — inheritor of those who “fought a war on the soil of America, under siege for decades and centuries.” He said he undertook his forthcoming book since he wanted to know his dad better “and realize why we are how we are.”

Beyond that, he wanted the project “to be a lighthouse for everybody right now who’s looking at the world and it feels insurmountable,” Dennis Jr. said. He told of the helpless feeling he and many Black people felt after the 2016 election – though his father predicted it based on his life’s experience with white Americans despite the outcome surprising Junior more — and he wanted to offer a “guidepost going forth” by telling of strong fighters who had come through just as hard or harder times before.

Both men said how much they enjoyed meeting early in the day with a Saint Michael’s class that Anderson-Douoning teaches about BIPOC women. Both in the class and in the Sutherland conversation, the three spoke in some detail about cultural notions of manhood and womanhood, what those terms mean, and the vital role women have played throughout Black history in advancing the Movement. They spoke also about the strength of the Black community being the extended family of a neighborhood, with everybody looking out for everybody else’s children and with elders passing along to young men and women what life required simply to stay alive.

President Sterritt and her husband, Bert Lain, take in Thursday’s Sutherland Lecture.

Said the younger Dennis, “Being Black and American and being alive IS resistance –My dad and I should not have the relationship we have with what this country tried to do to him and his life – to ruin his ability to be a father” — and that was true for Black families “as soon as they touched soil in America,” starting with slavery when men were sold away from their families.

On the notion of being a man, Dennis Sr. told of his grandfather who would squeeze his hand after coming in from the fields, saying that when his grandson could stand without falling to his knees, he would be a man. At age 16, he finally did it, and “he never hugged me after that” – but rather treated him “with a different kind of love and respect. I wasn’t ready psychologically for the transition. I felt the loss from being a child to being a man.” He pointed out that in America, we do not have a Veterans Days for Blacks who risked their lives in the domestic racism war with all its violence, risks and demands for courage that are part of any true war. This is one reason he and other Black men look at their families “as both biological and extended,” he said.

Inaugural Edmundite Fellow Jolivette Anderson-Douoning was a wise, animated and warm host for Thursday’s proceedings that she organized.

Dennis Jr. smiled in saying that while his dad never did the hand-squeezing test, his parents taught him about manhood by expressing love and pride in his achievements. As a result, he does not think about “checking certain manhood boxes” as earlier generations might have. He emphasized that women or LGBTQ people always have and still are getting as much or more done for social progress as any other affinity groups, so it has never been just men advancing the Movement and justice. He spoke of today’s odd and perplexing notions of manhood by which “wearing a mask makes you unmanly or you are too manly to go to the doctor — or a man should not be attracted to another man so I’m going to harm you because of the way he makes me feel.” So-called manhood in these cases, Dennis Jr. said, “is a weapon we continue to use and refuse to free ourselves from.”

One particularly affecting PowerPoint slide showed Black men in the ‘60s marching with signs that read, “I am a man.” Yet troopers with bayonets in the image pointed their guns at the peaceful marchers even as angry, volatile and jeering white observers behind them were menacing the marchers, and yet ignored.

Anderson-Douoning through the program paused when heroes of the Movement, famous or not, had their names spoken, and she invited the audience to “speak their names” in respect. She said, “At every corner of this story is a Black woman making sure that this Movement is going on – dragging black men to Freedom” which has been the case in the country since before Harriet Tubman, on through figures like Fannie Lou Hamer or Diane Nash and Oretha Castle.

A standing ovation for the Dennis men and their host after the Sutherland Lecture conversation.

Some stories from the evening’s conversation involved encounters by the Dennis men or the host with famous figures such as the actor Sidney Poitier or the singer Harry Belafonte in their civil rights work in the South, along with Bob Moses, and the inspiration they provided. Questions and answers from the audience near the end of the program probed such topics as dealing with fear, or the role of arts, faith and the church, and technology in the Movement.

Dennis Sr. told listeners: “The question you have to all ask yourself is, what type of America do you want to live in and want our children to grow up in? – we need to ask that of ourselves and decide what are you going to do about it,” since “what’s happening now is paving the way for the future.” It requires us to look around in our own communities and pay attention to who is on a city council or school board, he said.

Dennis Jr. said one goal of his book its “to make people feel not so overwhelmed.” Often stories of the Black experience end with people being murdered by the state, but he wants to emphatically say that “to be part of this Movement you don’t have to be killed.” Instead, “what you can do is the best you can do” – that is you don’t have to be Dr. King or Medgar Evers or Fannie Lou Hamer.

“You don’t have to die to be part of the Movement – it’s preferable that you live,” he said. “If you put a toe in, you will find a way.” In other words, he said, “I don’t think you need to quantify it, just do something and collectively the something will become enough.”

Faculty and staff join President Sterritt, the Dennis men and host Jolivette Anderson-Douoning after Thursday’s event.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.