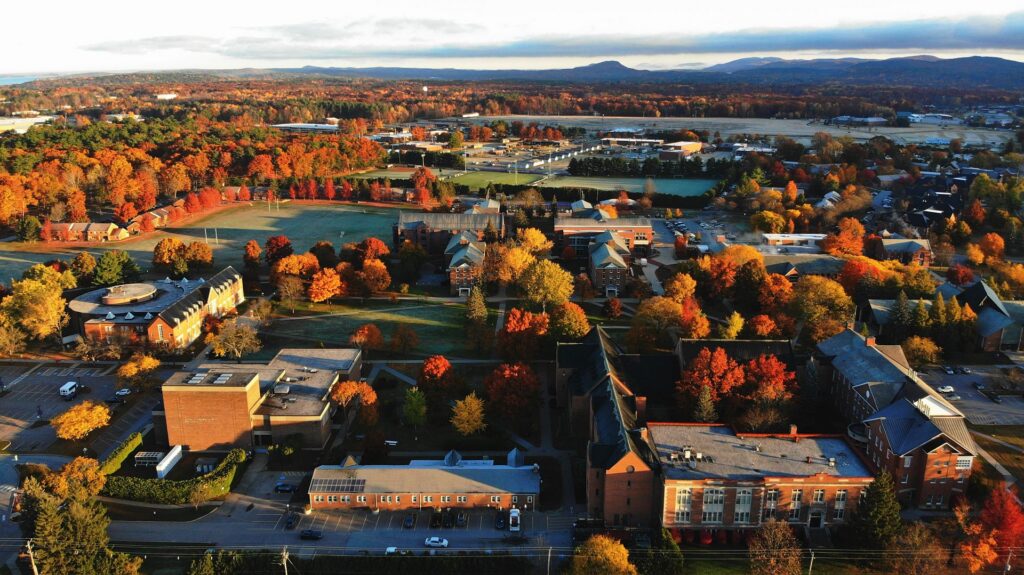

Mark Lubkowitz, left, and Valerie Bang-Jensen, in the Teaching Gardens earlier in their years of collaboration back in 2013. The top image behind the headline shows Mark researching corn with a collaborator a few years ago.

In July, Mark Lubkowitz of the Biology Department and Valerie Bang-Jensen of the Education Department learned that they and collaborators from major universities across the U.S. have been awarded a four-year grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Officially titled “Genome-Wide Dissection of Leaf Angle Variation Across Canopy in Maize,” the $2.3 million project allows its collaborators to investigate how leaf angle in corn can be genetically manipulated to increase both photosynthesis and crop yield.

“If you want to increase crop yield, and of course, everyone wants to increase crop yield because the amount of farmland we have on the planet decreases every year and global climate change is meant to accelerate that trend, you either have to increase farmland, which we’re not doing, or increase yield,” Lubkowitz said.

“You can’t make the sun brighter, but if you could capture more light, you’d be better off. It’s like solar panels, you can’t actually turn up the sun to get more energy from your solar panel, but you can make a better solar panel. Now think about leaves. What the group is doing scientifically is they’re trying to come up with a mathematical solution to determine where every leaf should be in a cornfield so you can get minimum competition.”

Given the small size of Saint Michael’s College, the vast majority of the work with the physical cornfields will be conducted at Cornell University, Iowa State University, and the University of Missouri where they have greater access to the necessary resources. “They’re planning out yields with robots that go up and down the field and measure the angle of every leaf, on every plant, every day, across hundreds of thousands of plants,” Lubkowitz said.

Mark Lubkowitz

While the larger universities involved in the project have more access to the tangible resources necessary to conduct research of this scale, the small size of Saint Michael’s is ideal for the dissemination of information, an equally important element of the project.

“We’re a ‘SLAC,’ or a small liberal arts college,” Bang-Jensen said. “And I think that what comes out of a SLAC can look really different. Some of the other people on the grant really don’t teach, they just do research. Mark and I both teach, so whatever we do always finds a way into our classrooms. I also think we are unique at a liberal arts school in that it’s an education professor and a biology professor teaming up whereas in these other places, I don’t even know if they know people outside of their departments. So I think that’s the real benefit to a small liberal arts college.”

Throughout the next four years, Lubkowitz and Bang-Jensen will utilize the College’s “SLAC” status to share the scientific findings with the greater academic community. “We’ll definitely have to publish some stuff, and the question with that which always comes is, am I writing stuff that will ever get read?” Lubkowitz said, laughing. “So we’re big fans of spending the time upfront where we will have the largest impact.”

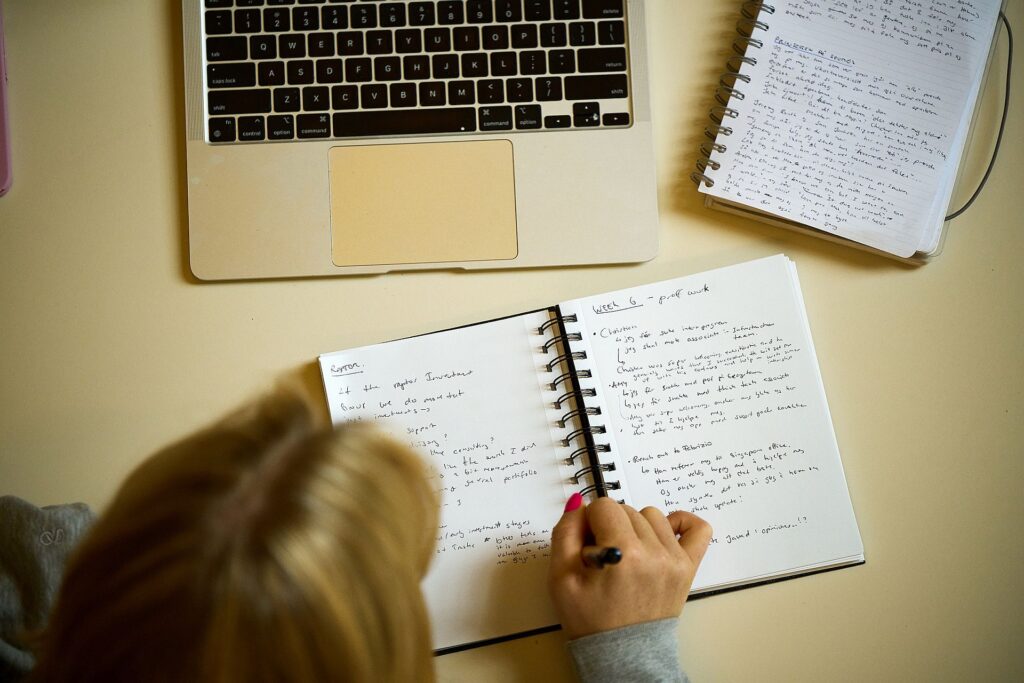

With this shared belief, Lubkowitz and Bang-Jensen plan to invite curriculum coordinators and K-12 teachers to workshops at the College each June for the next four years. “We’ve already started planning the first one, which won’t happen until next June, because we have to think about how what we’re doing relates to the science work that’s being done, and also how it relates to, essentially, our laboratory, which is the Teaching Gardens,” Bang-Jensen said.

Valerie Bang-Jensen

During their nearly 20 years of work together, Lubkowitz and Bang-Jensen founded the Teaching Gardens at Saint Michael’s, a place where literature and science can come together. “Mark and I continue to think about how to work across disciplines, because I’m not a scientist, I’m a literacy person in the Education Department, and he is a scientist,” Bang-Jensen said. “We’ve worked really hard over the years to help people see the science in children’s literature and how children’s literature can help you understand science.”

“One of the things that Mark and I talk a lot about are seven scientific concepts that you can find in any piece of literature if you code-switch. So for example, when scientists talk about cause and effect, literary critics call it plot. Or a scientist might think about systems which have a boundary and interacting components, but an English class might look at that as setting and characters. So there’s a lot of ways that people in both fields are describing the same thing, but using different language. Once you build that framework, all of a sudden you can talk more with scientists or others in a new way.”

Stemming from this notion of “intersectionality,” Lubkowitz and Bang-Jensen will take a multidisciplinary approach to the workshops each June, utilizing the Teaching Gardens, technology, and literature to create a seamless flow of guidance for the participants. Dedicated to continual improvement, at the end of each workshop they also plan to collect feedback from the participants and apply it to the planning for the next year’s workshop.

Mark and Valerie on campus in a recent photo.

Beyond the impact this project will have in their classrooms, Lubkowitz and Bang-Jensen will also hire two students each summer to work with them at the workshop, in addition to two to four students during the academic year to help with the lab work, Lubkowitz said.

In the long-term, the pair also plans to create a manual or written document discussing their processes and findings. They hope that through this writing their work will have a broader impact beyond those who attended the workshop.

Given that they are still in the early stages of the project, however, there is still much left unknown. “There’s always serendipitous events, discoveries, and setbacks that occur along the way of any project, and you hope that you can turn those into something insightful and useful,” Lubkowitz said.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.