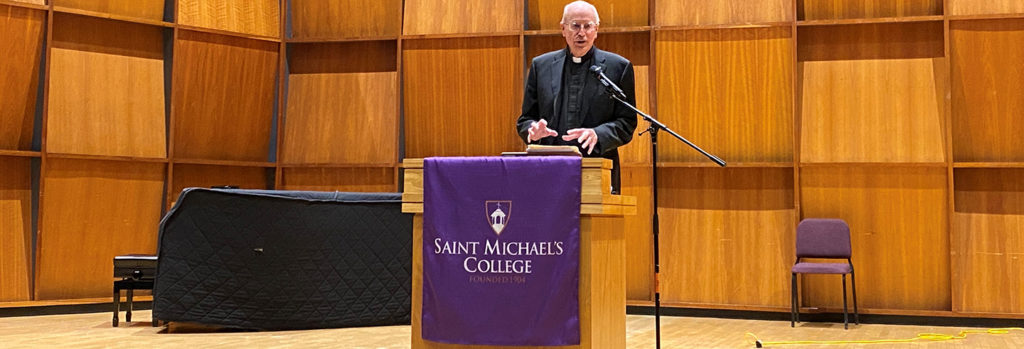

Fr. James Heft speaks in the McCarthy Recital Hall Wednesday, both in the large top photo behind the headline by Alex Bertoni and this image from Brother Tom Berube, S.S.E.

A leading expert on Catholic higher education acknowledged in a Saint Michael’s College campus lecture Wednesday that broad and deep challenges from modern culture reasonably raise the question of “whether Catholic intellectuals still have something worthwhile and distinctive to say to the world today,” and indeed, if Catholic colleges and universities have a future.

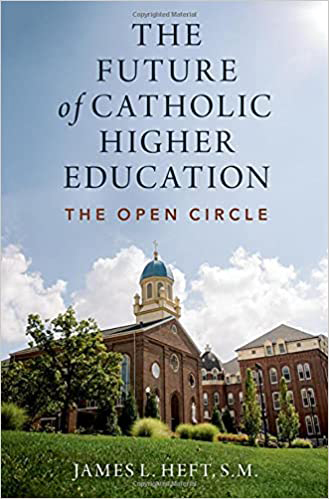

Fr. James L Heft, SM., founder and president emeritus of the Institute for Advanced Catholic Studies at the University of Southern California, believes the answer is yes to both questions. He proposed a college model from his recent book that he calls the “open circle” to sustain Catholic higher education in a way that entirely honors free inquiry, but also allows and promotes conversations across disciplines that incorporate a faith dimension. The lecture title was “The Open Circle: Catholic Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities.”

Introducing Heft was Edmundite Fr. David Theroux ’70, director of the Edmundite Center for Faith and Culture, who noted in his opening that several Edmundites at Saint Michael’s studied theology in Toronto with the speaker decades ago, making for an enduring connection that led indirectly to this week’s talk. Among them in the audience were Fr. Joseph McLaughlin ’66 and Fr. Richard Berube ’66.

Edmundite Fathers Richard Berube, left, and Joseph McLaughlin, right, were in the audience to hear a familiar voice from their long-ago theology studies in Toronto.

As Fr. Heft sees it, three basic models of higher education prevail in the U.S. today. Most prevalent is what he calls a “marketplace of ideas” model, shaped by secularism, government funding priorities and the consumerism of society. Even the most stable Catholic universities easily can be lured ever closer to that model by the prestige of elite secular private universities such as Princeton or Duke that had religious affiliation in their origins but now retain no meaningful connection to those traditions, he said.

Among challenges he identified as facing modern Catholic education include religious illiteracy among students and younger faculty, disaffected tenured Catholics, marginalization of the liberal arts by a move toward more professional education, or lay leaders not too well versed in Catholicism as an intellectual tradition.

He cited surveys in studies that failed even to ask college presidents what they understood the “Catholic dimension” of their institutions’ education to be, even if they mentioned such a dimension as important in a general way. These presidents in those surveys said faculty typically contributed least to making a Catholic dimension known, he said, which to him is unfortunate since faculty are around typically much longer that administrators to influence campus intellectual culture.

Another model that one sees more among some of the newer and more strictly doctrinaire and traditional Catholic colleges he calls the “closed circle” – that is, “a sectarian college welcoming only those from the same faith community.” These colleges “insist on fidelity, sometimes quite selectively, to teachings of the Church, and say little about Catholic social teaching,” while perhaps saying a lot about traditional sexual morality or abortion.

He said in what he calls his open circle model, “faculty and the student body need to be sufficiently distinctive to sustain a community on common discourse, but open enough to examine a wide variety of ideas.” An open circle, he said, “desires to be both distinctive and open.” A key difference is that to sustain a marketplace of ideas model is to embrace modern culture, while to keep a closed circle is to oppose it.

However, he said, it is more complex than just embracing or rejecting modern culture to achieve the open circle model. Challenges he mentioned were “balancing a robust Catholic identity in conversation with secular culture and other religions.” He believes this can foster more robust dialogue on religious and ethical issues than is possible at secular institutions. The model “welcomes those with other faiths or none who wish to contribute to the mission in ways they can.” He pointed out how St. Augustine was enriched by schools from pagan cultures in North Africa and Rome, while Aquinas drew on writings of the pagan Aristotle, or the Jewish scholar Maimonides. “In the open circle, Catholic scholars not only study texts of other traditions, but welcome those traditions in person among faculty and students,” he said.

More difficult is taking the next step and examining what those differences actually mean and what the differences mean to true believers within the tradition. He said today, it is “as common as the air we breathe for scholars to be content living life as though God did not exist,” while co-opting the ethical. He noted that an open circle approach shows that those without religion can be more moral than Catholic scholars in many cases – “There are moral atheists and immoral theists,” he said — given that the same human nature is embedded in each person for better or worse. “The sexual abuse crisis should cure Catholics of any presumption of the church’s moral authority,” he said.

The cover of the most recent book by Fr. James Heft.

So what, then, is the reason for a religiously affiliated institution?” he rhetorically wondered. Heft suggested an answer drawing on the fact that the first three of the Ten Commandments condemn idolatry since people worshiped false gods in ancient times and do so now – false gods such as money, power, prestige, fame, success and pleasure. “Most of us who follow false gods don’t realize we are doing so,” he said. Deciding what ‘true God” people should worship is not a question where answers are necessarily found even for Catholics in blind acceptance of authority, biblical or papal, he said.

Rather, he sees the best of Catholic tradition and the Gospel message leading to simple but profound goals for education, such as, “live simply, be mindful of the less fortunate or even be willing to lay down one’s life for others.” Belief is such a God calls for a particular way of living that would mean believers must be better than if they worshiped an idol, he said. Such a prevailing culture at a college as opposed to the more common marketplace model ultimately would benefit students, and also appeal to them and prospective faculty attuned to a Catholic mission so embodied, if properly presented, he speculated.

Speaking for himself,” Heft said, “I’m not that good, courageous or strong, and need all the help I can get. My understanding of God helps me be more loving and vulnerable than I would be otherwise … Jesus sets the bar high.” An open circle university opens conversations about spirituality along such lines, and about God, in ways impossible for secular universities, he said. He cited a philosopher who once remarked that, with India being the most religious country and Sweden the most secular by population percentage, the U.S. might be understood as “a nation of Indians ruled by Swedes.”

“What better place than a Catholic university or college” for searching discussions and intellectually sophisticated dialogue that open up the dominant culture to deeper realities, he said. Catholic education is capable of exploring these things in ways parishes are unable to as well, he said.

With all that said, he acknowledged, it is difficult for Catholic colleges to deal with the challenges of religious pluralism and secularism, without facing perhaps the most daunting challenge of all: the scarcity of Catholic intellectuals. “Intellectuals are fewer than those with doctorates,” Fr. Heft said. Catholic intellectuals, for example, make the Incarnation a focal point within a given discipline, with “sacramental imagination” and an appreciation for reason and faith and a desire to integrate knowledge with faith. That means, “Finding, hiring and developing such intellectuals,” he said.

In the speaker’s view, one “need not be a Catholic to appreciate the consequences of Catholicism,” and he said that Catholic intellectuals ideally affirm the roles of both faith and reason. Catholic colleges or universities, therefore, more often “speak of callings, not negotiated careers.” Critical thinking might bring one to to the doorway of faith, he said, but one must make an act of faith to step through, “continuing to think critically of faith once you have embraced it.”

Fr. Heft visits with Fr. McLaughlin before Wednesday’s talk. (photo by Brother Tom Berube, S.S.E)

In a question session following his lecture, an audience member asked Heft about key hiring considerations in his idea of open circle Catholic colleges. He said the real issue is how a candidate thinks about religion and its role.” So, he said, ask, perhaps, ‘are you comfortable being at an institution where ethical and religious discussions receive a particular attention?’” He personally would want to hire one who is interested in those questions, even if not religious. As with trees and roots, he said, “Where there is depth, there’s also flexibility,” and that is how an open circle Catholic college, never threatened by vigorous questioning, should be. Other questions from the audience dealt with being open to speakers with views at odds with Catholic teaching. Heft said he would be for it, just as C.S. Lewis at Oxford would have open debates with anybody on religious questions, leading ultimately to a wonderful education.

On another question, he spoke of the central importance that leadership plays in any open circle Catholic college. One general problem he commonly sees is that, “if any faculty member aspires to leadership, the rest say, ‘they’ve sold out on scholarship and gone for money and power.’” He sees that as “tragic” since it can lead the best faculty to go elsewhere, and the institution suffers.

In all such conversations, he suggested, “make sure the real issue is on the table to look at — talk about the elephant in the room and what we are dealing with. Let’s hear about it.”

Wednesday’s lecture was open to faculty and staff members of the college as well as students. The lecture was live-streamed and recorded. A link to the live streaming of the lecture soon will be available by contacting Fr. Theroux.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.