The last academic year was full of uncertainty for the Saint Michael’s College community. However, a few of the members in our community decided to amplify the unpredictability by studying abroad in midst of the pandemic. Maeve Kolb, class of 2022, was among the few who were able to study abroad their junior year in the spring of 2021.

“Reading and learning about disease in a place far removed from the diseases themselves is a much different experience from learning about disease in a place where you are incredibly vulnerable to them,” says Maeve Kolb ‘22, a Saint Michael’s College political science major from Old Lyme, CT.

“Reading and learning about disease in a place far removed from the diseases themselves is a much different experience from learning about disease in a place where you are incredibly vulnerable to them,” says Maeve Kolb ‘22, a Saint Michael’s College political science major from Old Lyme, CT.

Kolb found fulfillment in unexpected ways when she ventured out of the traditional classroom structure of the Saint Michael’s campus to study public health issues in Kenya through a program of the Vermont-based School for International Training that emphasizes experiential, non-traditional learning.

As was true for other students profiled earlier in this series — Olivia Hansen with an SIT program in Iceland, or Alexyah Dethvongsa, who ended up in Nepal through SIT rather than in India as she originally planned — Kolb had to be adaptable to last-minute changes because of the pandemic.

Before COVID came along, Kolb had planned to study post-genocide restoration in Kigali, Rwanda. However, the program was canceled last-minute, so she ended up doing the public health program in Kisumu, Kenya instead.

“I definitely do not regret studying abroad during this time, even though it wasn’t the country or program I had originally planned to attend,” she said. “I think that there was a lot of value in researching public health amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and I loved the experiences that I was able to have while in-country.”

She said that being faced with uncertainty and sudden change “was sort of par for the course in the pandemic anyway, so the sensations weren’t unlike what we have all been experiencing for the last year and a half. It was possibly a slightly stranger transition than what I had personally experienced before in the pandemic, just because it was a whole other culture that I was not familiar with that I had suddenly planned to spend four months in.”

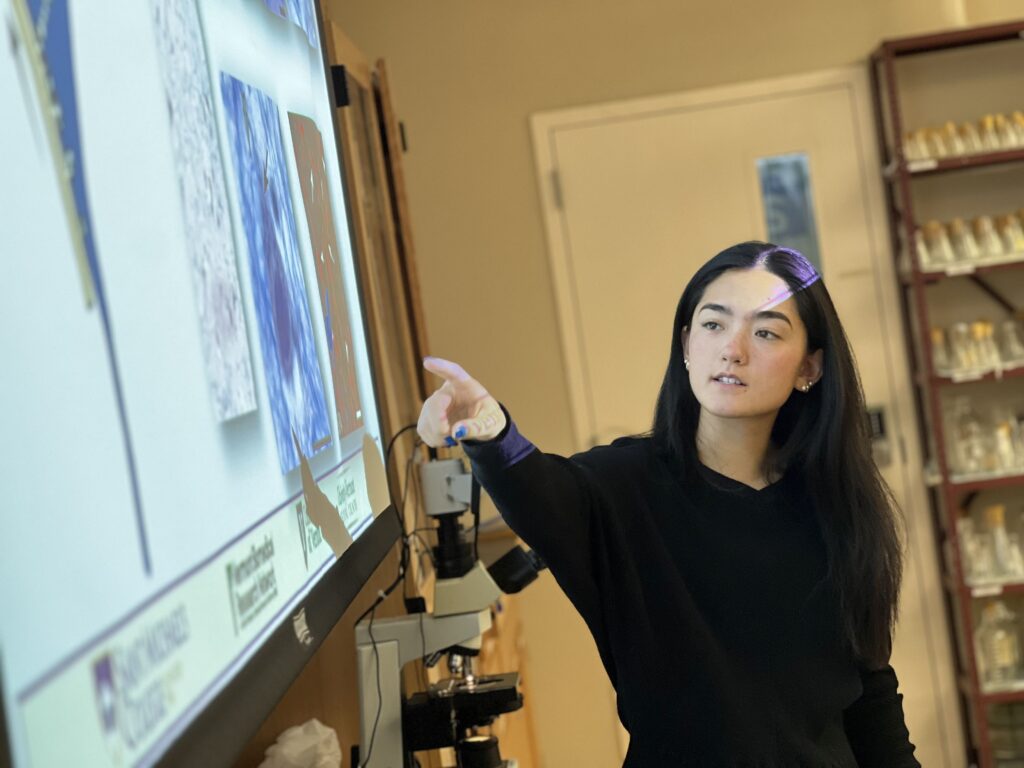

Learning language with fellow members of her program.

A typical day for Kolb included the five members in the program leaving and walking a few miles to a class to learn Kiswahili [a native language in Kenya, sometimes known just as Swahili]. The group would sit outside with their Kiswahili teacher, Walter, for about 90 minutes. “We also had a ‘house mama,’ named Cecilia, who would make us tea and Kenyan snacks in the SIT building after we were done with class,” she said. “We would often eat foods like Chapati, Ugali, Mdazi—among other things—usually accompanied by African chai.”

“After this, we would usually Zoom into our other four classes with Dr. Wandiga before heading out to walk, or tuk tuk [a mode of transportation] across town to our internships. Most of our time was spent in the Kisumu County Referral Hospital where we did a lot of observation and data entry,” Kolb said. “After leaving the hospital, we would usually grab a bite to eat at Java [essentially an East African Starbucks] with friends from the hospital before heading home. Some evenings we stayed in to work on our research projects and homework assignments, and other nights we would head to a place called Dunga Hill Camp—a quasi-restaurant on Lake Victoria.”

While living in Kenya, Kolb noticed a huge difference between the attitude around the pandemic versus the United States. “By nature of the climate near the equator, everything is quite spaced out and many things were permanently outdoors. Also, given that the average age in Kenya is about 19 years old, the morbidity and fatality rates of COVID-19 were drastically lower there,” she said. “As a result, the COVID-19 pandemic seemed insignificant compared to the other epidemics Kisumu is faced with — malaria, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, for example”

“Masks in certain settings were not only hard to find, but they were also very taboo. The assumption was that if you are wearing a mask, you must have COVID-19. Other places, like the hospital where we worked, required them. The police force was also heavily involved in enforcing the mask mandate and 8:30 p.m. curfew. Unfortunately, the current laws surrounding COVID-19 have only fueled the rampant corruption in the Kenyan police force,” Kolb said.

Pharmacies in in the area of Kenya where Maeve Kolb studied have a different look and feel from in the U.S.

Given that epidemiology was the main focus of Kolb’s studies, “disease was also something ever-present in my daily life during those few months. Sleeping underneath a mosquito net, brushing my teeth with a water bottle, wearing masks against tuberculosis, and working with many HIV positive patients was a huge hurdle for me,” she said.

“All of us were forced to face our humanity, as we have all done in this pandemic, in a way that I think was pretty transformational. It really wasn’t until I started making friends there that it all began to feel like a normal part of this new little life we had created,” she said. “This transition from initial feelings of fear and discomfort to really feeling like Kisumu was home was an incredible journey to see myself—and the other students—go through. Ultimately, I learned a lot about myself in relation to others and the world.”

In the end, Kolb believes if one has an opportunity to study abroad, one should take it. “Being able to form relationships and routines within the bounds of another culture is a real privilege. It challenges you and touches you in unexpected ways,” she said.

An African street scene captured by Maeve.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.