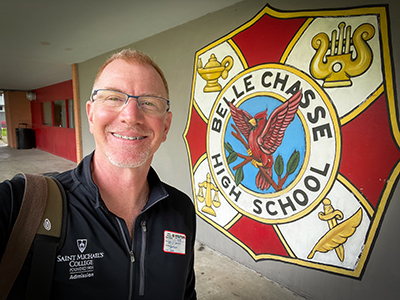

This past week at Saint Michael’s College, the Martin Luther King Jr. Society brought in speaker Arno Michaelis, author of My Life after Hate. Michaelis was once involved with a white power skinhead group and front man for the hate band Centurion. Fortunately, becoming a single parent inspired Michaelis’ realization about the truth of his hateful ways, which led him away from extremism and to the side of love.

The event took place on Thursday, September 7 in McCarthy Arts Center. Michaelis told his story to a full auditorium of St. Mike’s students, looking to educate the campus community on hate and how to combat it.

According to Michaelis, the root of all violence is suffering. People start to hate, he said, because they themselves are hurting in some way. To put this in perspective, he tells his own story of growing up with an alcoholic father:

“When I was a kid, I was suffering. The source of my suffering was rooted in an alcoholic household. My dad did more drinking than working, and it put a lot of pressure on my mom, and she was miserable. And I could feel her misery, it was tangible … I started to distance myself from her and from my dad, and from all the adults that really cared about me and wanted to help me. Of course, as I distanced myself, I made myself worse and started lashing out at other kids … I got a kick from it. It was like a rush, like any other kind of substance abuse,” Michaelis said.

His suffering led him to becoming a bully on the bus. When that wasn’t enough anymore, it became street fighting, then stealing and vandalism, then drinking. As he kept looking for something to give him a stronger rush, a better kick, hatred got the best of him.

“I think every single one of us who’s been through our teenage years had one moment when your parents or your teachers said something to piss you off, or something’s going wrong, and you’re just like, “I hate you!” For me, that feeling of ‘I hate you’ became another source of adrenaline. It was a rush to hate.”

So, Michaelis began to hate everything and everyone, from his parents and his teachers to the cops and the government. Unfortunately, this was his state of mind the first time he heard white power skinhead music. It drew him in, and so began seven years of hating black people and promoting white supremacy. He explains that the music was attractive to him not just because it was thrilling, but because “It pissed people off. I wanted to repulse people, I wanted people to hate me. Looking back, I can understand that that’s because I hated myself…. Rather than face my self-hatred and face my vulnerabilities, it was much easier to hate other people.” Hatred became such a powerful influence in Michaelis’ life, his daughter was conceived because he and his significant other believed it was their duty to produce white children in order to protect the legacy of the white race.

While suffering leads people to hatred, practice perpetuates it, according to Michaelis. In his presentation, he refers to the Oak Creek Massacre in 2012, when someone who was once a friend of his went into a Sikh Temple and killed six people. He believes horrible instances such as this happen when people actively practice hate and violence: “When you practice something, you become familiar with it… When you are familiar with hate and violence, the things that are most beautiful of all our human experiences, love, kindness, compassion, fellowship, all of those things become repulsive to you. Not just uncomfortable, repulsive.”

So if suffering and practice create hatred, what dissolves it? For Michaelis, the simple answer is kindness. It was kindness extended to him on the part of his black coworkers that forced him to face the absurdity of his beliefs.

“One day at work, I collapsed in the corner of the break room,” Michaelis says, “ I’m this miserable, pathetic, hungover fool, and I’m starving… and one of the black guys at work was sitting down, and he has his lunch… and he’s got a sandwich that he’s cut in half, and he sees me there in the corner and he’s like ‘hey, skinhead, you want half this sandwich?’ and I felt like an idiot.”

It was those people who “refused to be subject to [his] hostility, but rather defied [him] with kindness” who forced him to face his own hypocrisy. Michaelis mentions that a lot of what being involved with a skinhead group entailed was exhausting, but what exhausted him most was when someone he was supposed to hate treated him with kindness. This exhaustion eventually had him looking for an excuse to leave the “movement.” After watching friends murdered and arrested, Michaelis realized that sooner or later violence was going to take him away from his daughter. In that moment, he was freed from the trap of hatred.

“It’s very difficult to be kind to people who don’t deserve kindness,’ Michaelis recognizes, “But they’re the ones who need it most. I believe that the root of all human violence is suffering. Hurt people, hurt people. And I also believe that the next suffering person out there, on the verge of hurting themselves or hurting someone else, can be diverted with the right act of kindness at the right time.”

How comforting to know that something as seemingly trivial as half a sandwich can change the world.

Today, Arno Michaelis works with the organization Serve 2 Unite, which is dedicated to helping young people create inclusive, safe, and peaceful communities. He travels across the country sharing his story in an effort to combat the kind of hate he once spread. Michaelis’ story serves as a beacon of hope — as proof that truly anyone can change.

For all press inquiries contact Elizabeth Murray, Associate Director of Communications at Saint Michael's College.